Maja Daniels (b. 1985) is a Swedish photography-based artist. Маja engages in a multi-layered academic and artistic practice that incorporates sociological research methodology, sound, moving images, and archival materials, which is aimed at exploring the narrative and performative functions of each medium. Her work centers on history, memory, and how these notions influence our perception of the present.

Her first book Elf Dalia was published by MACK Books in the spring of 2019 and quickly gained international acclaim. It was nominated for the 2019 Aperture-Paris Photo First Book Award and was listed as one of the best books of the year by The Guardian, The Financial Times Magazine, The New Statesman, and a number of online publications. Additionally, the book won the Swedish Photobook of the Year Award in 2020. Elf Dalia was expanded into an exhibition (including a video installation) that is currently touring the world.

Maja Daniels began working on Elf Dalia in 2012 in her hometown of Älvdalen, researching the photo archive of early 20th-century local photographer Tenn Lars Persson, as well as issues connected to the miraculously preserved Älvdalian language, her own family history, and the mysteries of the place.

In 1668, a girl from the Swedish town of Älvdalen was accused of walking on water, which marked the beginning of the Swedish witch hunts. Twenty women and one man were executed in this region, primarily based on the testimonies of children. This story is further developed in the artist's next project — Gertrud. The project was published as a book, where Maja uses photography to rethink the history and myth associated with the aforementioned events.

It was a great pleasure for the Nizina team to interview Maja Daniels. In our conversation, the artist openly shared details about her projects, the nuances of creating a photobook and transforming it into an exhibition format, and her personal story. Enjoy the read!

A Russian version of the interview is also available via the link: RU Version

Looking back at your artistic journey, there’s a clear intersection of local and global, magical and documentary elements. How do you personally interpret this convergence of themes, and why do you find it important to engage with them?

My practice engages with the invisible ties between history and the present and how the representation of historic events, myths and experiences can impact the way we see and understand contemporary life.

I believe in the idea of starting off with something local and seemingly small or particular often have the ability of addressing something more broad and general at the same time.

I use photographic archives and historical documents/research in combination with my own image-making to investigate how my intervention with, and activation of an archive or event can raise alternative readings or interpretations and evoke questions around fairly abstract notions such as representation, language, science, myth, time and magic.

Perhaps one could think that constructs such as science, language, or magic are supposed to intellectually belong in different spheres. I don’t think that has to be the case and I want to create works that can allow for them to coexist together.

I find it creatively interesting to express concepts of, say, time by photographing such a slow place like the forest, or to comment on the idea of linear time and the process of history writing by engaging with archival works. It becomes a way to produce a counter narrative which is an important strategy in my work. I set up a framework relating to history with the aim to expand and critique some of what that framework holds. For me; it’s a process of undoing the given. However, it’s not just a stance or an opinion, I am also creating something new, and I feel like photography becomes an appropriate tool since it has this kind of claim and illusion of inherent truth that I love to play with.

Specifically, the photographic archive has this kind of weight of documentation that is naturally built into it and my aim is to question that, or to play with it somehow, and to evoke new stories by using these same tools, but to shift how we consider or see them.

Basically, I want to position my work in conversation with established knowledge (history, archive, linguistics, sociology) whilst producing a subjective response that is tied locally to heredity and personal experience.

What was your entry point into the exploration of myths? How do you relate to the idea of magical thinking in contemporary society?

When looking at the connections and performative potential between historical events and contemporary life, I became interested in myths due to their cultural function within community-building (oral history for example), and how they connect the landscape (specific places) with history (specific events).

In this process, I also started looking at the connection between photography and myth. A myth can be used to make sense of the world and oral traditions are often based on myths and folklore as a way of learning and sharing, but these myths exist within the boundaries of the unspoken. They are open to interpretations but refuse to be fully locked down or understood. In some ways they are resisting. Photographs function in a similar way. The core of what is expressed in an image lies somewhere in the unseen or in its silent associations. The myth and the photograph thus have a powerful, but also dangerous potential in their trickster way of silently stating the ‘obvious’. What I try to do in this series is to play with these notions by allowing them to join forces; using photography as a tool for mythmaking.

The book and exhibition ‘Gertrud’ uses the history and myth surrounding the 12-year-old girl Gertrud Svensdotter from Älvdalen as a starting point. In 1668 she was accused of having walked on water. This event became the ignition of the Swedish witch-hunts; a period of mass hysteria and horror in Älvdalen and its neighbouring regions. Today, it is both fascinating and difficult to understand how a 12-year-old girl could come to play such a central role in one of Sweden's most macabre historical events. Her fate raises many questions.

The aim of this work is to use history as a framework to explore an alternative outcome in the present. In ‘Gertrud’ I try to resurrect the strong, women-centred culture that the witch trials fought so hard to eliminate. Of course, I use my own imagination to create this world but the point is to make it felt, to invite the reader to feel it too and to simply join me in a desire to re-imagine it all on our own terms. Most of the images in this series are created through interventions in the landscape where I shape my own rituals and create new mythologies of sorts, beyond the already existing ones. They become a way for me to expand on and challenge certain historical constructs and to show how a visual narrative can recreate our relationship with both past, present and future.

For me photography is a magical space that can challenge established knowledge, make time collapse and resculpt or reconfigure the boundaries of the world as we traditionally know it. By engaging with the myths related to the ignition of the witch-hunts and creating a response to them in a contemporary setting, I construct an alternative world which, I hope, can provoke thoughts about how ideology has shaped our understanding of history and of the present.

What does working with an archive mean to you — is it about reconstructing the past, resisting dominant narratives, or uncovering silenced stories?

All of the above!

In a previous interview, you mentioned that you descend from speakers of the Älvdalian language, which is now endangered, though you no longer speak it yourself. Would you say that the photobook Elf Dalia uses this story of cultural loss to reflect on a wider, global sense of loss?

Yes, absolutely. Having spent time in the Älvdalian forests with my grandparents since childhood, the question around the language Elfdalian and its unique situation started growing on me after having spent years living abroad and feeling quite rootless. The work actually made me pack up and leave the life I was living in London at the time in order to move into our small family cabin built by my grandfather in Älvdalen. As the very idea of community and nature become increasingly abstract, fluid and complex concepts, in ‘Elf Dalia’ I try to engage in a deeper understanding of what community and loss means, and how we navigate our place within it. I am also inspired by a kind of resistance (perhaps imagined, perhaps real) that I personally associate the community of Älvdalen with. Having preserved their own language Elfdalian (the closest language variety to Old Norse) against all odds, the fact that it is still spoken today perplexes historians and linguists. This resistance is something I also associate with the fact that the Swedish witch-hunts began in this place.

In Elf Dalia, you create a dialogue with the photographs of Tenn Lars Persson, a photographer and author working with the history and myths of Älvdalen. How do you think this dialogue would have changed if you hadn’t had the opportunity to work on the project in Älvdalen?

If I had not found the works of Tenn-Lars Persson, I am not sure I would have made ‘Elf Dalia’ and thus not felt the urge to pursue the work and make ‘Gertrud’. Both works is a collaboration between his and my work, curated by myself. ‘Elf Dalia’ centered around the notion of language and how to expand the notion of a world connected to speaking a specific language. This world was constructed as a kind of dialogue across time between myself and Tenn Lars Persson.

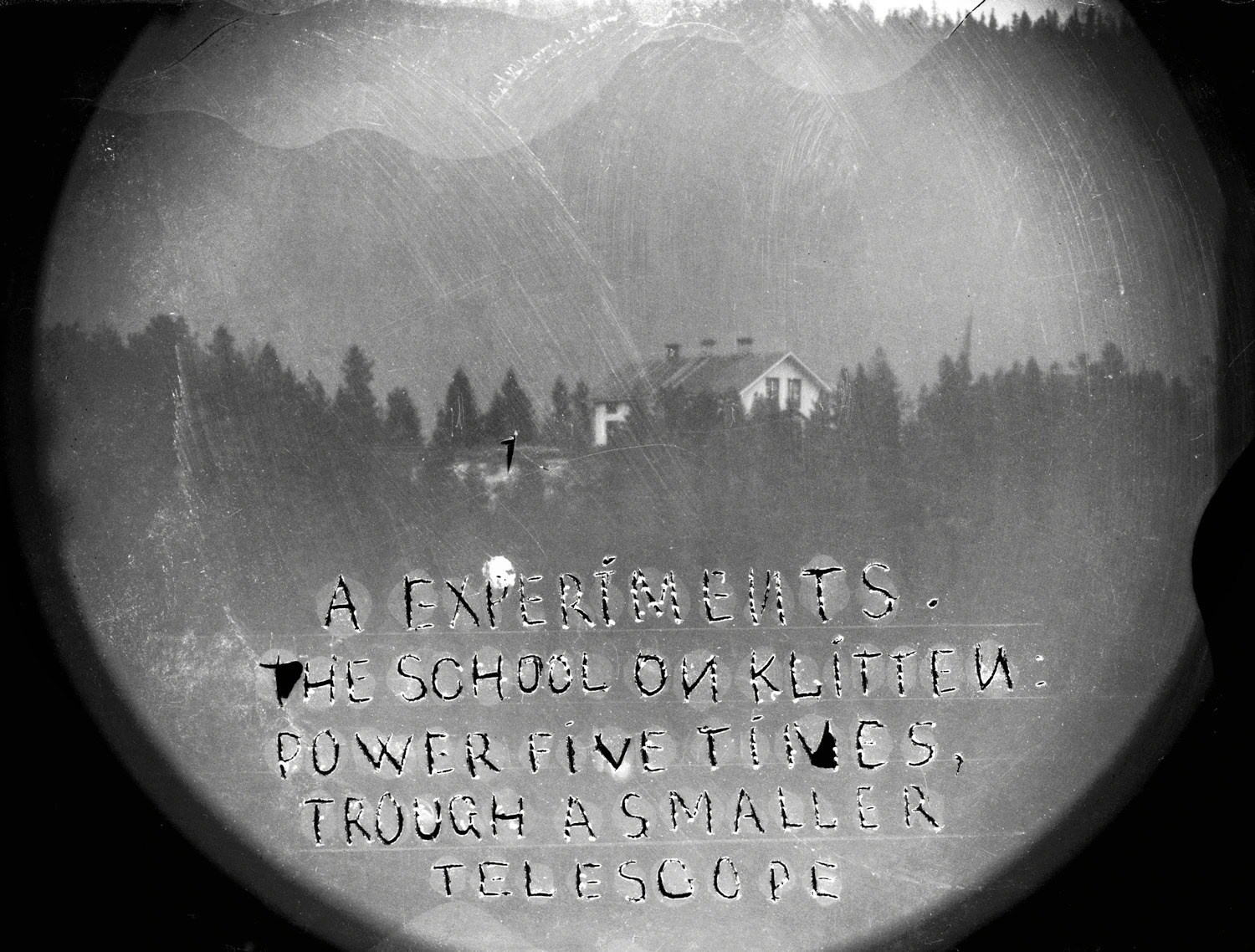

Then, in Gertrud, as I focus on myth, I extend this notion of dialogue by continuing to use the archive of Tenn-Lars but this time the distinct dialectical framework of colour (me) vs. black and white (Tenn-Lars) is replaced by a more fluid and blurred line between us, very much in order to illustrate how mythology works.

In Gertrud I am also interested to play with visual tropes relating to archival materials, and highlight how they influence the way we read and understand an image. The inherit truth-claim of a seemingly older photograph is so powerful that we naturally start to look for Gertrud in each gaze even if the archival photographs were made 250 years after Gertrud was alive.

Yet, all of a sudden, the work of Tenn-Lars and myself becomes a vessel for Gertrud to gaze back, across history, and to highlight those forgotten qualities of a culture that formed a way of life so potent that it had to be silenced. And. as these gazes of girls and women are combined and multiplied, a part of this myth is made undone. The multitude of possible faces spanning across time from 20th century to today, becomes a way to highlight and question the oftentimes taken for granted documentary qualities of archival material and to point the finger back onto the construction itself.

How did you approach selecting the photos for the book, and how was the sequence constructed — did your initial vision evolve as you went along? Did you uncover anything unexpected in the final stages?

I tried to just follow my desire to make work in the forest, the forest pastures around Älvdalen and not think too much too soon about sequence etc. Once I decided to go back into Tenn-Lars’s archive and to look specifically for Gertrud there as well (in the same ways that I had found her in the gaze of the girls and women I had started photographing) things started to make sense. Then, I built on different visual layers of the story and gradually started to test sequences. I think unexpected connections kept coming up once I started working with the archival materials, mainly in terms of how to construct the book and how to build the sequence.

Were there decisions in the book that appeared by chance but later became central?

I think most of the images I make appear by chance. I try to let my desire lead the way when I shoot. I am sure most people who work with photography can relate to how things just seem to happen in front of you when you are present and open to receive. I also try to invite chance into my images by leaking the film, allowing for the light leaks to interact with the motif and add an extra layer to it.

What role does the video installation play within the overall project, and what were your goals in going beyond the photobook medium?

The two pieces of film I show in the exhibition are connected to how I see editing (in filmmaking) and sequencing (in bookmaking) as mythmaking tools. The story is created as much when sequencing and when shooting. Sometimes I shoot more or add more material from archives if the edit/sequence requires me to do so. One of the video installations is focussing on an 11 year-old girl who I met at a residency in Norway. She was the first girl I saw Gertrud in. The other video piece is using a house as a site-specific holder of a myth unfolding.

Then, the exhibition also consists of a sculptural installation piece with the intention to use the specific conditions of an exhibition (people coming to a specific place to engage with the work) to continue building on the myth I have created around Gertrud in the images.

So, for the exhibition, I created coins with a specific symbol that was found in a firehouse in a forest pasture near Älvdalen; a place central to the witch-hunts. I found the figure in a book about local myths and, interestingly, the origins of the inscribed symbol was unknown.

In the book it says «This demon or mythological figure, with cyclopic eyes, four legs and a pipe in their mouth, was found inscribed in the firehouse in the Black mountain Forest pasture, perhaps is it a remnant from the witch trials in Älvdalen and Lillhärdal in the 1660-70, perhaps its even older».

This I think goes to show how silent myths are and how this can be dangerous. It is easy to just claim that this figure is a representation of the devil, and thus inscribe it into the narrative of «bad». However, when I look at it, I see a strong matriarchal figure… a woman… a leader of rituals… with the pipe (that blows smoke) and the sticks… the magic sticks… to me it is also a shape-shifter: a figure in the middle of trasition…

In the exhibition, visitors were invited to discover these coins in the black box standing next to the exhibition’s centrepiece: a large water well. With its blank surface it refers to the myth about Gertrud but if the visitors choose to offer the coin into it, they create a new way of relating to a historically loaded symbol, charging it with wishes and hope which becomes a positive, slightly surreal, performative action. The work thus reflects on how pre-Christian beliefs were demonised during the witch trials — while opening space for new, more hopeful interpretations. The act of participating in the ritual of the exhibition continues to build on the world I created when making the work, seeking to use the flexibility of imagination as a provocation in and through time and thus create an alternative interpretation of the established history of the witch-trials and of Gertrud, as well as to illuminate the specific culture of silence and ignorance that these historical events are rooted in.

Then, the figure also became the cover of the book, which turns the book into a grimoire.

When your projects transition from a book to an exhibition, how does your perception of the work change?

I find that it grows and evolves for each iteration and each medium used. I — quite naturally -learn new things about it all as I adapt the work to different viewing experiences.

In the project Gertrud, you reconstruct the story of a 12-year-old girl, Gertrud, accused of witchcraft in 1667 — a terrifying moment that marked the beginning of a 30-year witch hunt. How did you discover this story, and what does it mean to you personally?

The story of Gertrud was part of the framework in my first book ‘Elf Dalia’, but upon publishing that book, I couldn’t let her go, I kept coming back to what I had learned about her particular destiny. Having grown up hearing my grandmother speak of ‘Gertrud who walked on water’, I always thought of her as a girl with magical abilities (a bit like Astrid Lindgren’s Pippi Longstocking if that says anything to you) so when I started researching the period of the witch-hunts, delving into the church records (the only documented source we have from that time), to find out about the actual proceedings of history, I felt the urge to create an alternative history for Gertrud, to free her from the role she had come to bear in history. I started noticing 11-12 year old girls in my surroundings, seeing glimpses of Gertrud through them and I began photographing them.

Gertrud’s destiny is particularly heartbreaking given the role she had to play and how she was treated. According to the the church records, she, an orphaned 12 year-old who had been sent to live with her aunt in Älvdalen a few years earlier (thus an outsider) gets accused of walking on water by a 9 year-old boy after they had a fight over a piece of bread while herding goats together. She then gets taken into custody by the church, is sleep deprived, sexually harassed and questioned for days. After this she is the first person to admit to sorcery. (normally accusations were rejected. If an accusation was denied, there were no repercussions). In the process of admitting to witchcraft she was then forced to name others, the people who had taught her, who then subsequently were arrested and accused as well. One could only speculate around why Gertrud admitted and how it came to ignite the preceding events in history, but it seems clear to me that her destiny was hijacked and used to induce fear. Her confession came at the right time and place. It gave the ruling powers a valid excuse to clamp down on the culture of pagan beliefs combined with strong, independent women and their knowledge that had to be stifled due to the growing power of the Christian church.

I also found out very recently that two of the 19 women who were first accused of sorcery (or witch-craft) and later executed happen to be in my direct lineage. This could be pure coincidence, or it could have something to do with my unconscious desire to engage with it all as well.

The forest in Gertrud is not just a landscape but a special space of memory and myth. Why was it important for you to conduct most of the shooting in the forest?

I personally think of the forest as a holder of time and memories. Trees are among the oldest living organisms on earth. In Älvdalen you can find one of the oldest spruces in the world (Old Tjikko), it is about 9500 years old. So, perhaps unsurprisingly, spirituality and magic has for centuries been indistinguishable from nature itself. Nature was the place of worship, it was treated with respect and love, but also with fear. However, it was very much woven into daily life.

In the 17th century life was very much bound to the forest and specific forest farms (forest pastures) became the central sites for the developments of the witch-hunts. In these places women lived independently from men in order to take care of cattle who grazed in the forests during the three months of summer. This was a practical arrangement since all land in this region had such poor soil that all land needed to be used to grow crops; none could be spared for animals to graze. In these isolated and solitary places, women gained a lot of independence and autonomy as well as a sense of commune. They also developed knowledge around plant medicine since it was a given part of life to survive so far away from ‘civilisation’. This part of everyday life in the region resulted in women who were used to speak up and who knew their worth. This was something the church had a hard time accepting and it was a leading reason for the witch trials to erupt. Gertrud for example, grew up in such a forest pasture culture.

Today, not only do many of these forest farms still remain, many are also still in use. Now, they represent one of the most ecological ways of life there is with their small-scale combination of forestry and agriculture. To me these places become a sort of portal not only to the past but also to the future. I find them so fascinating because they allow us to think about the future without relying only on ideas of how technology is going to save us.

My aim when using photography to create these historically inspired, contemporary myths based in the forest and in the forest partures, is to embrace the surrealist desire to ‘reenchant the world’ and by doing so, to highlight how deeply engrained and dependent we are on finding new ways beyond a capitalist worldview (and means of production) to reconnect with our environment in order to envision new ways of being in this world. Through an engagement with my tangible surroundings — I try to question, and stress the danger of simplified narratives related to history and science. For example, that our way of understanding what we might lose when speaking about climate change and threats to the environment is broader than its environmental impact; the forest is also a holder of memory, language, history, culture, mysticism and imagination.

Materiality plays a significant role in Gertrud: different paper weights, some images shown full-bleed for a cinematic effect, and others placed fragmentarily on white pages. How do you see this materiality connecting to the ideas of myth, memory, and imagination?

The material choices were made to enhance/highlight the shifts within the book’s sequence. Touch is a sense that is activated when reading a book and we wanted to enhance the tactile shifts between the different ‘chapters’ in the book. I was quite particular about the overall full bleed cinematic effect of the book but, as with most effects, they become more powerful if they are also disrupted by another kind of rhythm. When the sequence suddenly halters over the white pages where smaller images of girls holding hands are placed fragmentarily across the pages creates (in my opinion for this particular book) a way to alter the impression of time as we enter a part of the book where time could be felt to move a bit differently or at a different pace.

Final question: during the process of working on your books, do you have any small rituals or even quirky habits that might seem amusing from the outside?

Even if the work makes sense to me in retrospect, I don’t really know what I am doing whilst making the work. The whole process often feels like a strange game or ritual and my main ‘job’ within it seems to be to not censure myself too harshly or to let too much criticism and doubt stand in the way of the actual making. So, when I make work I often speak to myself aloud, which can be confusing to a sitter.

Photos of projects and exhibitions: Void, MACK, Maja Daniels