Moe Suzuki was born in Tokyo and studied photography at the London College of Communication, University of the Arts London. Upon returning to Tokyo after the Great Eastern Earthquake in 2011, Moe self-taught bookbinding skills and started a career as a visual artist, creating numerous personal projects of hand-bound art books. Her primary medium is photography, which is mixed with archives, illustrations and film to tell complex narratives in the books and installations. Her work engages with themes of community, disability, and spirituality.

Moe’s photobook SOKOHI won the LUMA Rencontres Dummy Book Award in Arles in 2021. A year later, the photobook was published in collaboration with Chose Commune.

We were lucky to interview Moe Suzuki, and our conversation touched on the meanings and motivations behind her art, as well as her thoughtful dialogue with viewers. Enjoy the read!

Did your everyday interactions with your father change as you immersed yourself deeper into working on Sokohi? Was there anything new or unexpected that you started to notice—things you hadn’t paid attention to before?

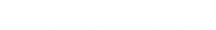

It all began when we moved in together in 2018. His glaucoma was progressing quickly at that time, which made it increasingly difficult for him to get things done by himself. I also had a son, so we decided to move in together.

One morning, he asked me to pass him his coffee cup, but his hand just grabbed at thin air. This made me realise just how much he couldn’t see — far more than I had expected. This made me start working on this project, delving into the world he was actually seeing.

In Sokohi, blindness appears not only as the loss of sight, but also as a space where imagination begins to work, establishing contact and understanding of another’s experience. While working on the book, did you feel that your own way of seeing shifted as well — re-living an experience that was initially inaccessible to you?

I started thinking about what 'seeing' actually means. At first, I was upset that my father and I wouldn’t see the same things as before, but I later realised that it's impossible to know if two people looking at the same thing perceive it in exactly the same way. We never know. This made me realise that being able to see doesn't necessarily mean you can see things. Similarly, being visually impaired doesn't necessarily mean that you can't see things. Looking at my father with glaucoma made me realise that seeing isn't only done through our vision, and that we often don't see the full picture through our eyes.

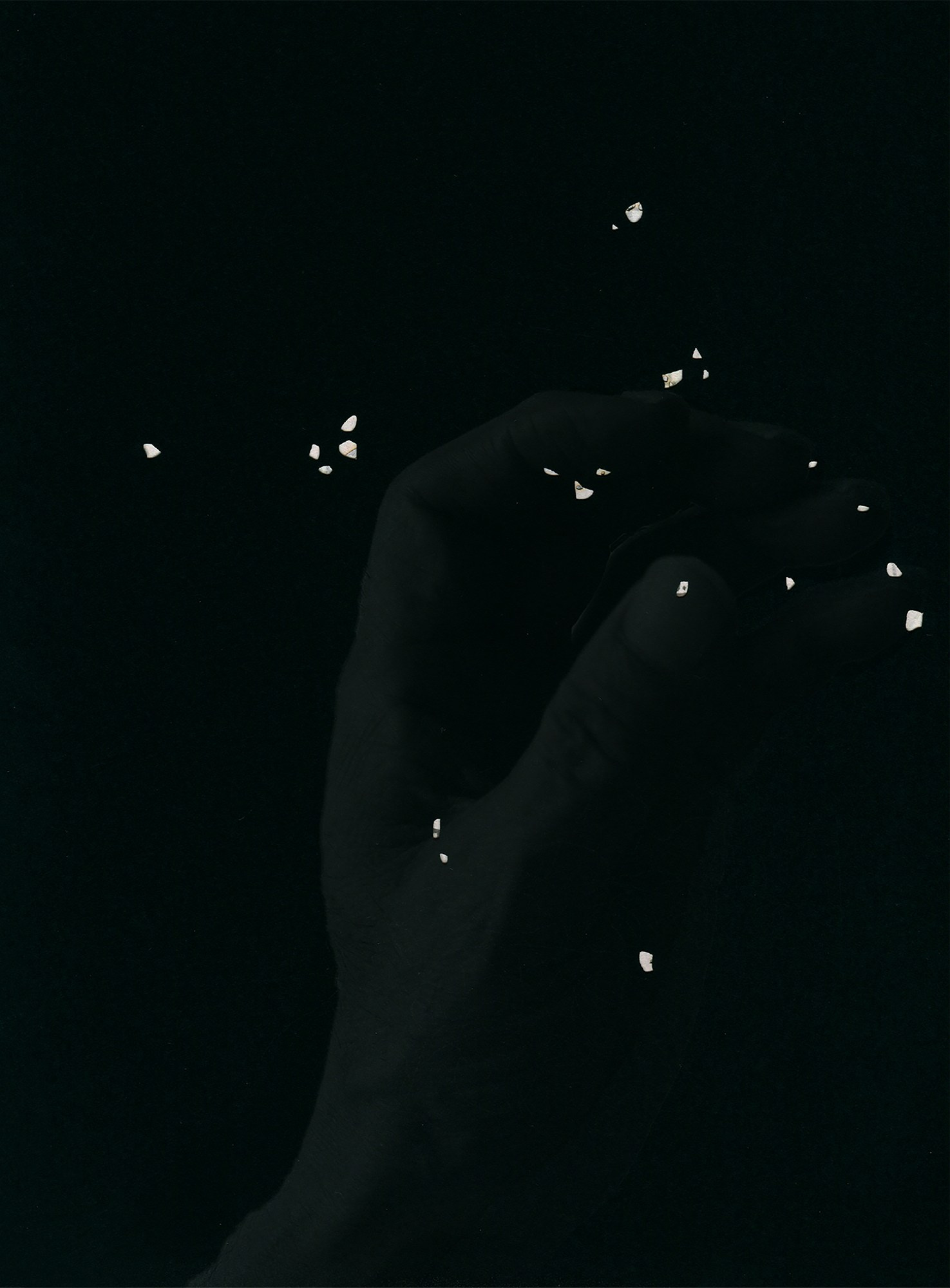

Laser-cut holes in the pages, mimicking blind spots, make a very strong impression. How did this idea come about? Was it an intuitive decision from the start or the result of a search? Were there other ideas or experiments along the way?

I often asked my father what the world was like for him after he developed glaucoma. He described it as if it were covered in tissue paper or a curtain, with excessive contrast and so on. What struck me most was that, when he tried to focus on something, he could see lots of tiny holes, just like in Yayoi Kusama’s drawings. Initially, I overlaid dot drawing on images, but later started laser-cutting prints, particularly of old family photographs and diaries. The burnt holes also symbolise what he could not see anymore, illustrating the damage to his optic nerves as his glaucoma progressed.

Why did you decide to abandon this idea in the Chose Commune edition? Was this due to technical limitations or your own evolving sense of the book at that stage?

Yes, there were technical limitations for the large edition, but more importantly, I believe that both Chose Commune and I were ready to create SOKOHI's new storyline at that time.

The laser-cut artist edition was created when my father's glaucoma was progressing rapidly. He underwent surgery to prevent further deterioration, but it was unsuccessful. In retrospect, it was a time when he was experiencing mild depression, and our focus was solely on our loss.

While I was working on SOKOHI with Chose Commune, however, his glaucoma progression slowed down. He learnt how to use his iPad and iPhone by touch and voice alone, and started a whole new life going out with friends who were also visually impaired or with carers to the cinema, exhibitions, holiday and so on. Losing your sight is not the end of the world! He moved forward into something entirely new. I therefore wanted to create a new storyline for SOKOHI to document his journey, and Chose Commune gave me the opportunity to do so.

What did you find most interesting or revealing about collaborating with Chose Commune on Sokohi?

As I said in my previous answer, editing the new sequence was always exciting. Chose Commune also gave a new focus to the images taken by my father on his iPhone, which added an important dimension to the project. It was the time of Woodshock in Europe, which resulted in some challenges when it came to choosing and holding paper, but I also found that a new layer of meaning always emerged in the photobook, even from things you weren't expecting.

Do you typically work on books in an intensive, immersive mode, or is it always a lengthy, years-long process? How do you usually recognize the moment when a project is finished and it’s time to let it go?

It is usually a long process. I work on the sequence of my photobook on a wall, on a computer screen and in a printed and bound book, sometimes viewing it again and again as a movie. It is also very important to me to look at the pages of my sequence being turned over by a third person, as this gives me a more objective view of it. Once the storyline's rhythm really flows and settles, I can see its completion (but of course, there are many more design aspects to consider…).

When working on your books, do you have any little rituals or even quirky habits that might seem amusing from the outside?

Maybe the same answer as the above???

Your projects often originate from something personal, but over time they reveal a broader context — cultural, social, political. Is this a way for you to locate points of tension within society? Do you feel that a personal story can exist outside such a framework?

Exactly! A deeply personal story always connects to the broader social context, and vice versa. I feel that we delude ourselves into thinking we know everything exposed to a sea of superficial information every day, which stifles our active thinking. Perhaps my small resistance to this trend is my way of visually creating narratives that allow us to touch and imagine someone’s personal life and the social context behind it.

Your most recent book, Aabuku, explores the invisible contamination of water and soil in Okinawa — the toxic legacy of PFAS left by US military bases — and the lives of people connected to these places. At what point did you realize you wanted to explore this issue and create your own personal statement?

My mother actually lives in Okinawa. One day, she told me that she had stopped using tap water for drinking and cooking because of contamination. That was the beginning. The more research I did, the more paradoxes I found about this island and PFAS: beautiful nature alongside hidden contamination; a useful chemical that is almost essential to our lives and yet toxic. I then decided to develop this story into my project.

For Aabuku, you spent several years conducting an expedition and doing research, collecting scientific reports, archival materials, and stories from local residents. Could you elaborate on how this process unfolded? Where did you start, how did you find people and work with their stories, and how did you navigate the contaminated areas? How did the people you interviewed respond to your interest?

At that time, research into contamination was crucial, as the issue of PFAS contamination was not well understood in Japan, and no government regulations existed regarding drinking water. Also, stories relating to US bases in Okinawa are always sensitive. Those who supported the bases might target this story and anyone involved in it, so I had to be extremely careful when conducting the research and collecting evidence. After listing all the spots contaminated by the bases, I started searching for people with a personal connection to these spots. These included local elders who conduct rituals at the well, farmers who use groundwater for irrigation and people who drink tapwater without any doubts. Some were introduced by my mother, some I contacted on SNS after reading their posts, and some were introduced by other interviewees. I always carried a dummy book of Aabuku in progress and showed it to people when I first met them, after which they started telling their own stories.

How do you envision the future of the Aabuku photobook? Is there a particular audience you feel this book especially needs to reach?

Following my work in Aabuku, Okinawa, I have been working on sequels in Okayama and potentially one more location in Japan where PFAS contamination has been identified, but which was caused by different sources to the bases. I am planning to publish these photobooks in a trilogy in late 2026. I have reached a point where I strongly feel that this story should not be limited to the context of art galleries or art books just to be consumed. How can an art book be made available to a wider audience beyond this? At what price? Where can they be sold? Which opportunities or events could be utilised? I have been searching for a way to make the Aabuku trilogy, a book that tells a story to which everyone in the world is more or less related, more accessible to a wider audience.

What gives your artistic practice the deepest meaning today? Are there things you now permit yourself as an artist that were previously off limits?

How to visually express a personal story that can only be told by that person.

Photos of projects and exhibitions: Мoe Suzuki

Photobooks: Chose Commune, Reminders Project